How we grow a tiny garden with very simple techniques

Here I describe the series of activities we perform to grow and maintain our tiny rooftop garden of 3.5 m2. Our key objectives are to maximize biomass production, maximize ecological diversity while using techniques and knowledge as simple as possible.

As it turns out, our practice more or less falls into the category of bio-intensive gardening , preparing in small scale for our project of an experimental food forest!

, preparing in small scale for our project of an experimental food forest!

I present the main tasks that we perform to take care of our garden, the way we do them, and the reasons why we do it this way. Such a list of farming or gardening activities can be called a technical itinerary.

Table of content

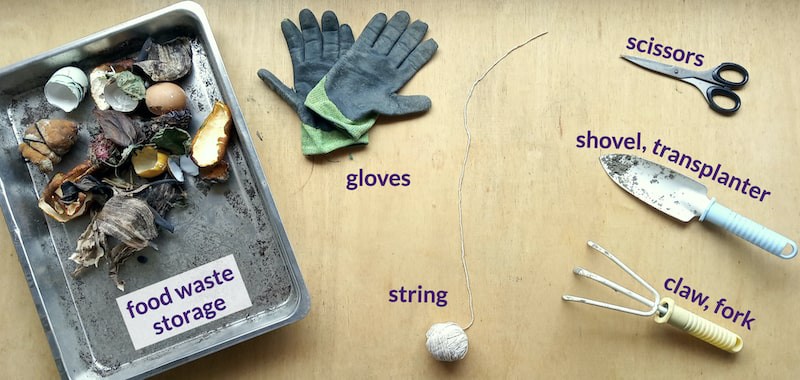

A simple set of tools

We use a very simple set of tools to maintain our tiny garden.

- Claw or fork. To decompact soil, break soil aggregates, or remove strong roots.

- Shovel or transplanter. To move soil or dig holes for sowing seeds or transplanting seedlings.

- Flat food waste storage. To collect our food waste before we bring it to the rooftop.

- String. We use it to tie plants on stakes, like tomatoes.

- Scissors. To cut food waste chunks into small pieces, cut the string, trim plants, or harvest leaves.

- Gloves. We can do without, but they are useful when the weather is cold or when we have sensitive skin.

Plants choice and spatial repartition

There are many potential aspects to account for when wondering which plants to grow and how to organize them spatially and temporally.

For instance, we can organize a garden following permaculture design principles . One important strategy to integrate into a garden design can be the concept of companion planting

. One important strategy to integrate into a garden design can be the concept of companion planting . That is, to put together plants that can grow in synergy, because they use different nutrients; they find their resources at different soil depths; they attract insects beneficial for the companion plant, or on the contrary, repel insects that are harmful to the companion plant, etc.

. That is, to put together plants that can grow in synergy, because they use different nutrients; they find their resources at different soil depths; they attract insects beneficial for the companion plant, or on the contrary, repel insects that are harmful to the companion plant, etc.

Although I find these interactions passionate, I have to say that this concept of companion plants gives me headaches. I tend to be a perfectionist and as soon as I start to imagine a beautiful garden following a good design and companion planting principles, my brain bugs in front of such complexity, and I end up doing nothing.

That is why, here, we intentionally didn’t design anything before starting. For a small garden like this one, the design is anyway less crucial than for big permaculture farms. Instead, we decided to give more weight to learning through observation, which is, by the way, another important strategy in permaculture.

Oh, fun fact before starting: without a design, our garden tends to look a bit wild. We don’t mind so much, we find it poetic and bucolic. One day, however, I realized that someone had stepped on our garden and broke some plants! Apart from being surprising, as there is nothing very interesting to do when stepping on a raised-bed garden, it was also an unexpected confirmation that our gardening style looked very natural. This person obviously didn’t realize that this was, indeed, a vegetable garden.

It is one of the risks of growing things with a natural look! In order to avoid future such adventures, I installed a few bamboo sticks to create a mini-fence. If it is not clear for some people that this place is a very serious agricultural research station, I thought, a barrier should be a more broadly recognized concept. It seemed to have worked so far!

So now, let’s see how we choose plants and how we organize them spatially, with no design.

Plants choice: we grow anything we find

In terms of plant choice, we try to maximize plant diversity.

When we started the garden in August 2020, we bought a few seedlings of spinach, lettuce, and cabbage. We sowed seeds that we had collected from fresh vegetables, such as squash seeds. We also found many kinds of local seeds in a seed exchange market. We germinated seeds that we bought as edible food, such as adzuki beans, chickpeas, and tiger nuts. We planted tubers or bulbs that were spontaneously sprouting in our fridge, such as ginger, turmeric, and garlic. We also tried to plant directly some vegetal parts like the head of a pineapple or the head of a daikon radish. We tried plant cutting to propagate basil and sweet potato leaves. And after a few months, tomato and squash seeds from our food waste are sprouting.

As you see, as soon as we find something, we try to grow it.

One trend, however, is to favor perennial plants over annual ones when possible. These will develop larger root systems, they will tend to produce a higher amount of biomass, and they definitely save the repetitive preparatory work of germination, and so on.

Meanwhile, we also try to keep the wild plants that grow spontaneously. It is a very important part of our technical itinerary: observing what grows naturally. Then, to identify which species it is, and to look for potential uses we can make from it.

For instance, we have some edible weeds, such as this Cardamine from the cabbage family (Brassicaceae), which tastes like rocket salad.

Other weeds may have medicinal properties or other beneficial properties. We are going to identify them over the next months…

Spatial repartition of plants: we target a high plants density

In terms of plant location, we try to maximize biomass production.

The basic idea is to collect as much ray of sunlight as possible. For this, we try to plant many plants for the ground to be completely covered by leaves. On one of our two plots, we even tried to add a bamboo structure to grow 2 additional layers of vegetation above the ground level layer.

Having a too dense top cover may reduce the growth of plants at the lower levels. But that’s fine. If we reach this state, it will mean that we indeed reached a maximum where we collect all the available solar energy. Our tiny garden will then look like a tiny tropical forest with a dense canopy! Wonderful.

Then, we will have a few options. For instance, trimming the top layer to allow a little bit more sun to reach the lower leaves. Ideally, these trimmed leaves would be edible, but if they are not they will provide decomposing biomass to support soil life. Another option could be to find plants that thrive in very shadowy places. Or, why not trying to grow mushrooms directly into the mulch? As fungi do not need light to grow.

When we sow new seeds or plant seedlings, we try to think about the best location, depending on the knowledge we already have. For instance, I saw that taro grows well in wet and shadowy places. A farmer told us that chayote needs a lot of water. Turmeric can produce large and vertical leaves, so it seems a good idea to plant it in the middle of sweet potato whose stems and leaves are developing more horizontally, etc.

needs a lot of water. Turmeric can produce large and vertical leaves, so it seems a good idea to plant it in the middle of sweet potato whose stems and leaves are developing more horizontally, etc.

We do the best we can with our current knowledge, without looking for more information. We just try to do it and see what happens.

Similarly, when a plant starts to grow spontaneously, we can either let it grow where it sprouted or transplant it where we think it could be a better location. In both cases, we observe what happens, and if necessary, we try to adjust later.

In summary:

We try to grow anything we find, to increase plant diversity. We tend to prefer perennial plants, and we value spontaneous plants a lot. We want to maximize biomass production, so we do not mind if plants are very close to one another or if there seem to be too many layers of leaves. We do think about the best location to place each plant, but without thinking too much. Our focus is more on learning from action and observation. We didn’t do any preparatory design. Hence, the garden develops slowly, but hopefully, we will end up with a more resilient and natural design.

No protection against insects

There are several potential strategies to protect plants against insects naturally.

For instance, some flowering plants can attract parasitic wasps that lay their eggs inside the eggs of herbivorous insects. Hence the population of these herbivorous insects is regulated by the parasitic wasp leading to less damage to the crops. I had the chance to observe this kind of plant-insect complex interactions when I was doing an internship in Kenya back in 2007. In an article, I described the epic life of a cowpea flower (in French), its parasites, and the parasites of its parasites!

In our tiny garden, I drilled many holes in the bamboo trellis in order to create a variety of shelters to increase insects diversity and plant-insect interactions.

I have seen, for instance, that in spring in Taipei several kinds of wasp like to lay eggs in such drilled bamboo poles.

The thick layer of food waste mulch also provides different spots and shelters for insects to hide.

Here again, we don’t really try to favor a specific plant-insect interaction, but we rather want to favor any type of interaction by increasing ecological diversity. This way, complex ecological phenomena can happen, even with simple skills and knowledge.

If a greedy insect species attacks some of our plants, we want to observe how the ecosystem reacts. Will any predator or parasite counter-attack and regulate the population of this greedy insect? Will the attacked plant species find a way to adapt? Will some of the seedlings appear to be resistant to this specific insect?

We are okay to lose some of the production, as it supports ecosystem life and diversity and offers us very insightful examples of ecological interactions to learn from.

In summary:

We do not apply anything on our plants to repel insects, and we do not actively try to attract specific beneficial insects. We try to favor complex plant-insect interactions by increasing decomposing biomass amount, shelter diversity, and plant diversity. If some insect happens to eat our plants, we try to observe calmly and see how our mini-ecosystem reacts !

Fertilizer: food waste mulch

The only input that we add to our garden is our food wastes. We apply them directly on the top of the soil, as a mulch, about a few centimeters thick (~1 in).

When we lived in the forest on a large land, we had a quite successful compost with very little work and problems. In the city, we tried different kinds of composting systems, but each time we faced many difficulties.

We tried vermicompost , but the temperature was too high for the worms, and they died. We switched to bokashi

, but the temperature was too high for the worms, and they died. We switched to bokashi . But after the fermenting period of a few weeks, the volume of food waste was still significant. At the time, we didn’t have a tiny garden to bury the fermented food waste and we ended up accumulating more and more fermented food waste on our balcony! We were grateful when black soldier flies

. But after the fermenting period of a few weeks, the volume of food waste was still significant. At the time, we didn’t have a tiny garden to bury the fermented food waste and we ended up accumulating more and more fermented food waste on our balcony! We were grateful when black soldier flies fortunately invaded our bokashi. The larvae of this fly can process significant amounts of food waste in just a few days. But, again, it turned out to be too difficult to control the temperature of the bucket. Not happy with the conditions we offered, the poor larvae invaded our balcony, looking for a better host!

fortunately invaded our bokashi. The larvae of this fly can process significant amounts of food waste in just a few days. But, again, it turned out to be too difficult to control the temperature of the bucket. Not happy with the conditions we offered, the poor larvae invaded our balcony, looking for a better host!

Then, we got access to our rooftop spots. Since that moment, we simplified our system: we accumulate our food waste in two flat containers on the balcony.

Food chunks dry more or less quickly depending on the weather. As they are well-aerated, they don’t ferment and there is no smell. After a few days to a week, I cut the biggest pieces with scissors, I put everything in a bucket and I bring it to the roof. There, I simply apply these small chunks of partially dry biomass on the top of the soil.

This biomass plays the role of mulch, slowing down weeds growth, and maintaining steady soil temperature and soil moisture.

A few days later, the food waste chunks are already covered by fungi. They start to decompose, providing lots of nutrients and carbon to soil microorganisms and insects.

It is a process a little bit similar to using ramial chipped wood . While compost tends to be a bit acidic and bacteria-rich, well aerated ramial chipped wood tends to favor fungus development over bacteria. In our case, the main difference with fragmented wood is that food waste is much richer in nitrogen than wood chips.

. While compost tends to be a bit acidic and bacteria-rich, well aerated ramial chipped wood tends to favor fungus development over bacteria. In our case, the main difference with fragmented wood is that food waste is much richer in nitrogen than wood chips.

A high level of nitrogen is an advantage in terms of soil fertility, but it can also favor the fast development of fungi. This can be more challenging for plants that fear wet conditions and fungi.

For instance, these poor sweet potato stems were colonized by the same fungus that was growing on our food waste mulch.

Instead of stopping to add our mulch, or trying to treat our sweet potatoes, we just waited and observed. It seems that some of them found out how to adapt, as they are now fungi-free, even with a lot of food waste still decomposing all around.

I like to cut the food waste into small pieces before applying them, to avoid bumping against big chunks with the tools later. Cutting in small pieces is the most time-consuming part of this process. But overall, this system works for us as we find it more simple than composting on our tiny balcony.

We eat mostly organic food. When we buy non-organic food, we sometimes discard the peels in the normal rubbish bin, just to avoid an unnecessary accumulation of toxic compounds in such small gardens.

We do not add any synthetic product, nor even organic storebought fertilizers.

No watering

Over 7 months, we have only used a few liters of water, to water seedlings when we transplant them to the garden on a sunny day.

We like to think that our tiny garden is an autonomous tiny forest. We can leave it for a few days or more, and whether it is rainy or sunny, it will keep developing happily. If some plants appear to struggle too much with the climate, we prefer to replace them with other species more adapted. In brief, we like to focus on building resilience to our garden, rather than trying to compensate for its weakness by watering and working more.

Of course, in terms of water, the wet climate of Taipei is an asset. But in winter, there are some periods during which it does not rain for a few consecutive weeks. So, water management is still a useful issue to consider.

Another asset is the significant amount of soil that the built-in containers are holding. That is, more than 50 cm of soil depth (20 in) able to retain a lot of moisture.

Then, to further improve the resilience of our garden we try to focus on practices that increase the water-holding capacity of our soil and limit water loss.

The main factors we can work on to maintain a high and steady amount of water in our soil are: increasing soil porosity, avoiding bare-soil, and favoring perennial plants.

Hereafter I describe what we do for these 3 points.

Increasing soil porosity with roots and insects

A porous soil will store more water in its pores, compared to compacted soil. In addition, roots can grow more easily in porous soil. With long roots, plants can find water in deep soil layers even in case of a drought.

We can decompact the soil at the very beginning when we prepare the garden. In our case, we only uncompacted over about 20 cm deep (8 in) when weeding the first time. As it is a raised-bed garden, we usually don’t need to step on it, which limits compaction.

Taproot is a kind of root system where a main strong root grows downward. Common examples of taproots are carrots and radishes. A taproot can have the ability to transpierce strong layers of compacted soil and reach deep water and nutrients. Hence taproot plants can be very helpful to decompact soil. Some weeds also have this kind of root system, such as dandelion. In our garden, we have maintained so far a few dandelions for this purpose.

Of course, soil insects and earthworms are doing a huge work of decompacting soil. In order to favor their activity, we simply need to provide food for them through our food waste mulch.

The action of roots and insects to decompact soil can take time. But it does not require any specific effort from us and occurs softly, without a strong and sudden disturbance.

Avoiding bare-soil with ground cover plants and mulch

When the soil is bare, it is in direct contact with sunlight and wind. Sunlight heats the soil which may kill some insects and microorganisms and of course, dries the upper layer. Wind also has a strong drying effect as it favors water evaporation.

A porous soil already reduces the evaporation rate because there is no continuity between soil aggregates. In compacted soil, in contrast, sun and wind can literally suck water even from deep soil layers due to capillarity forces in a finer and more continuous soil matrix.

The main strategy we use to limit soil water evaporation is to have many layers of leaves preventing sunlight from reaching the ground in the first place. As we want to maximize biomass production, we try to have several layers of leaves. For instance, sweet potato and mint cover the soil very well while producing edible leaves.

Sometimes wild plants can also be very useful as ground cover plants, like this small wild roquette.

If we haven’t planted anything yet in a spot, we just let some specific weeds conquer and protect the space.

The second strategy we use to limit soil water evaporation is to apply a mulch. As we already try to collect all sunlight on the canopy, the mulch is mostly useful to protect soil from the wind. The drying effect of wind is especially significant at high altitudes such as on the rooftop of buildings.

Favoring perennial plants and frugal plants

Plants with deep roots are more resilient as they are likely to find water in deep soil layers even when it does not rain. As we saw, they also participate in maintaining soil porosity that, in turn, increases the capacity of soil to retain water.

Perennial plants have such deep roots because they can grow over long periods. In addition to requiring less work and tending to produce more biomass, they are hence a good choice for water resilience!

Of course, frugal plants, that don’t require a lot of water to grow and survive, also significantly make our garden more resilient.

Our aloe vera seems very happy, wild mint already prospers and we are also trying to grow dragon fruit!

In summary:

Except when transplanting seedlings, we don’t water our rooftop garden. We like to think of our garden as a resilient mini forest that does not need us to thrive. The wet climate of Taipei and the significant amount of soil in our raised-bed containers are clear assets. But we also try to improve soil water holding capacity and limit water loss. For this, we increase soil porosity by supporting root and insect development. We limit water evaporation by developing a dense canopy and covering the soil with food waste mulch. And we favor perennial and frugal plants.

Weeding = Harvesting

Ideally, I dream of a tiny food forest garden, where we would gather abundant food while never working against the spontaneous ecological dynamics. In such a wonderful garden there would not be any difference between weeding, trimming, or harvesting. Because everything growing would be seen as useful.

The fundamental idea behind this is to try to enjoy as much as possible the natural processes. The work of the gardener is hence much more modest and reduced. Instead of planning and organizing with plenty of knowledge and skills, the gardener is observing what happens spontaneously and selects the processes and plants that serve him.

We haven’t yet achieved this goal, as we take time to develop the garden slowly. But here is one situation to illustrate what I mean.

When I arrive in front of our garden, I start to explore below the mini canopy. What’s happening there? Are there new spontaneous seedlings? If I find a small plant of tomato, wild roquette, or squash, I check if I could favor its development by trimming the canopy above. As the canopy is mainly made of sweet potato leaves, I put them in my harvesting bag. Everything I do plays different roles at the same time: trimming the canopy is also selecting new seedlings and also harvesting edible sweet potato leaves.

To reach such a situation, we still needed to weed significantly at the beginning. We removed, for instance, some grass with very entangled weeds. Now, when I see small seedlings of grass, I remove them very easily before they are too big. Weeding small seedlings is very easy in porous and soft soil. If we do have to weed, then we leave the weeds on the mulch where they will protect the soil and provide nutrients to soil life.

Then, we tried to let some edible plants colonize space as much as possible. Thus they capture sunlight, protect the soil and limit the growth of non-edible spontaneous plants. We made a bamboo trellis for one of our two plots, in order to sustain several layers of canopy.

Now we are trying to observe what grows and select the plants that we find useful.

In summary:

We like to think of our garden as a tiny food forest providing abundant food with limited input of work. To reach this state, we try to develop a high density of edible and useful plants. Once the system works, we like to see the gardener work as merely observing what happens and supporting the spontaneous beneficial dynamics. Ideally, there is no difference anymore between weeding, trimming, or harvesting.

Are you also growing a tiny food forest with very simple techniques?

I would be very interested to know how you do it and what your outcomes are!

Did you enjoy this post?

Great! Then, you may also like to read our project of a Mediterranean food forest, a few design ideas on how to grow ‘living walls’ to shape landscapes, or an essay on ‘invasive plants’ where I invite you to think like an ecosystem.