Acorns and their germination. A contemplative exploration

ˬ˯vᐯ˅ˇ⌣ ᘁ ᥎ᨆ⏝ࡍ⩗ᨆ⌣˘ˬ᥎ᐯᨆ⌣ᘁ⩗ᨆࡍ˯

This post is from Mésange, my weekly ‘popup’ newsletter, from October 2022 to March 2023. < Previous | Next >

For some unknown reason, I’ve been interested in acorns for a few weeks now. Maybe a little because I saw them accumulating under an oak tree not far from the tiny house, on my parents’ land.

As I studied this topic, I realized there was so much to say about acorns, that I would have to write you three letters.

This first letter is rather contemplative. In the second letter, we will eat acorns, — yes! — like so many civilizations in the past. And in the third, we will try to ferment them.

Still on the tree, the life of the acorn is full of surprises

I walk in the forest. While still on the oak tree, I see that acorns have amazing fates.

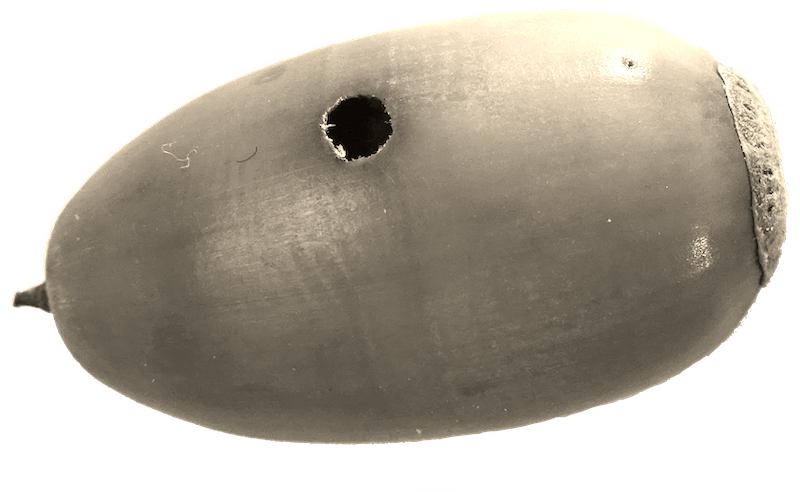

Some get punctured by worms.

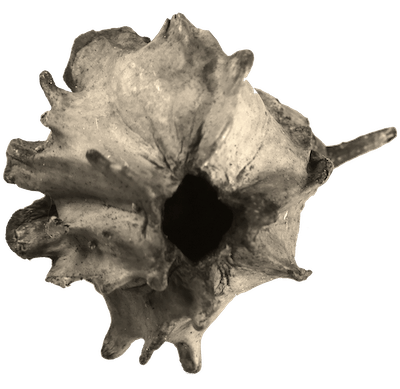

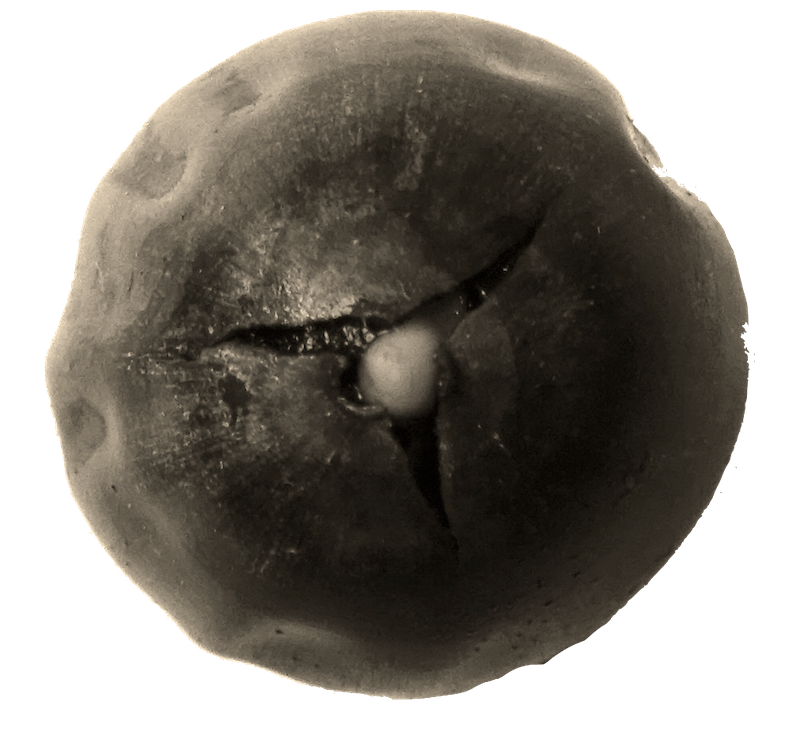

Others turn into dinosaurs. This incredible shape is a gall, that is, a growth produced by the tree after a wasp laid eggs on it.

It reminds me of another complex interaction between plants and insects that I observed in Kenya (article in French) on cowpea flowers.

Here, the wasp’s egg laid on the acorn produces hormones that trigger the formation of this gall. From what I have read, the details of the interactions between the egg and the tree are still unknown1. That’s perfect, it leaves me room for imagination.

Does the egg manipulate the tree, for it to build this stylish little fortress? Or is the tree cleverly locking the egg in a golden prison to prevent further damage? Or, is the tree preparing a cozy nest for its friend the wasp, who will protect it from another insect when spring comes?

But the life of acorns is full of surprises. Having escaped the worms and wasps, the acorn discovers the squirrels! Oh, here is one of them, working around the tiny house…

Not only squirrels, but jays, some woodpeckers, rats, mice also store acorns for the winter. And, since they don’t retrieve them all, they participate in the dispersal of the oaks.

Freshly on the ground, the acorn germinates

As I continue my walk, I realize that the acorns fall before the oak leaves. Lifting the dead leaves reveals a multitude of acorns, visually hidden from animals and protected from the cold. In this moist and shaded layer, the acorns find the perfect environment to start germinating!

The oak’s strategy, I think, is to store a maximum of energy in a large seed. And, as soon as it finds itself on the ground, the acorn wastes no time. Even without the spring sunshine, it can rely on this stored energy to start growing.

This is a risky strategy, since such a large seed, rich in starch, oils, and minerals, is highly prized by animals during the winter. Or could it be a subtle strategy, with several objectives: using animals to disperse the acorns much farther than the tree or the wind could do?

But, by the way, how do squirrels keep the acorns they bury from sprouting?

I found an answer in a scientific article published in 1982. First, squirrels prefer to store varieties that germinate later, which gives them time. And for early varieties, they sterilize the acorns, by cutting off the small radicle on the tip, before burying them2.

That simple!

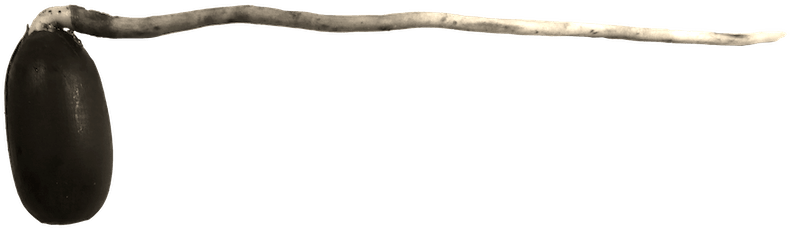

The taproot of the baby oak tree shows up

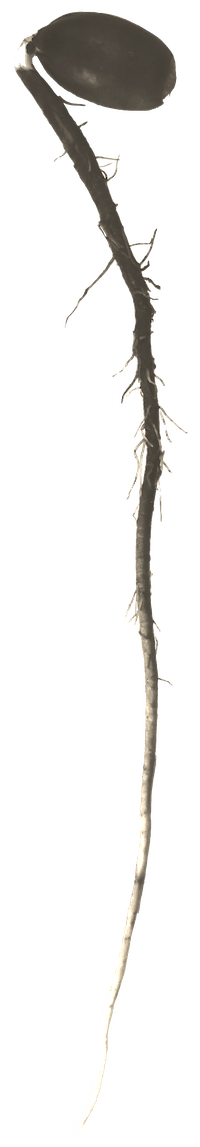

Still observing under this carpet of dead leaves, I wonder how deep the root of an acorn can reach at the end of November…

The acorn sends a taproot, that is, a root that goes straight down. Such a root will allow the tree to have good anchoring and direct access to underground water. A transplanted oak tree will not have this very deep root, which will make it less resilient to drought.

I see many rootlets just showing up. Others are a few centimeters long. With amazement, I find some of more than 10 cm long (4 in)! And the longest one, here on this picture, is already 20 cm long (8 in)!

At this speed, I wonder which depth an oak root can reach, at the beginning of spring, before its very first leaf has even appeared…

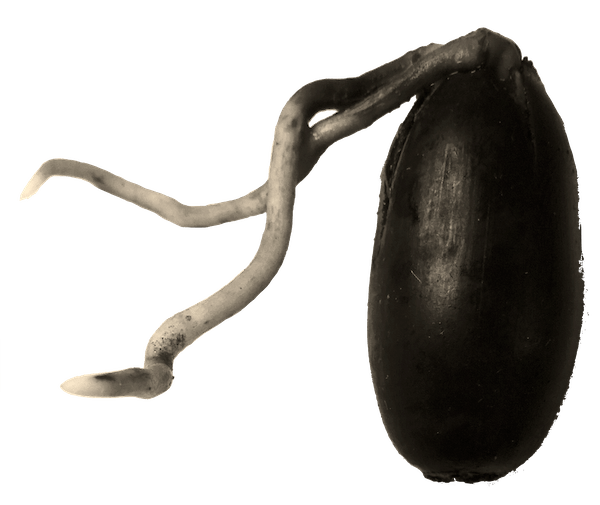

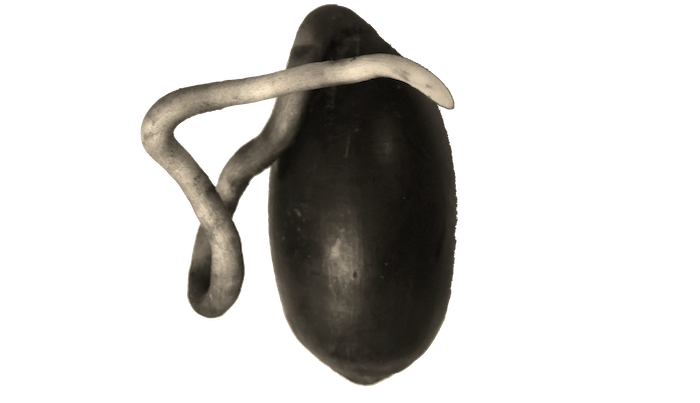

Each taproot has its own shape

I contemplate these small roots.

Some don’t really start in the right place. And yet, they grow.

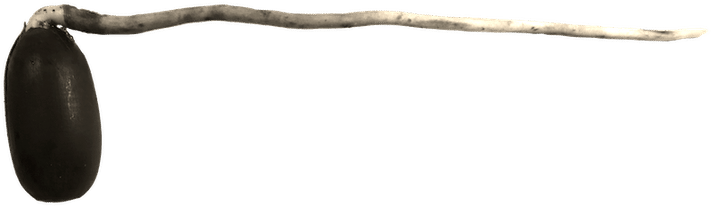

Some look a bit shy.

Some look smooth, others bushy.

Contrary to what I said, a taproot is only straight in theory!

Imagining these roots as human life trajectories…

As I contemplate these little roots a bit more, I imagine that I am watching the trajectories of human lives.

Some are not sure which way to start.

Some trajectories surprisingly start from the same seed…

Oh, here’s a straight one! How strange it looks, among the others!

Apart from a few rare straight ones, a trend seems to emerge: these life trajectories are all crooked!

Each on its side, they seem to be asking, “Uh, excuse me, which way is it?”

- Stone, G.N., Schönrogge, K., Atkinson, R.J., Bellido, D. and Pujade-Villar, J., 2002. The population biology of oak gall wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Annual review of entomology, 47(1), pp.633-668.

- Fox, J.F., 1982. Adaptation of gray squirrel behavior to autumn germination by white oak acorns. Evolution, pp.800-809.

- Previous experiment (7/26) : The fridge of our tiny house

- Next experiment (9/26): Acorns, tannins, and humans. How acorns have been prepared as food in History